Sometimes history can be hard to imagine. It certainly helps when someone who has lived it can talk about it.

The number of survivors actively still talking about their personal experiences are dwindling, but their descendants are carrying the torch to make sure today’s students know: the Holocaust was very much real, and it needs to be talked about.

Eighth graders at Sangaree Middle are currently reading excerpts from "The Diary of Anne Frank." and discussing the Holocaust in their English/language arts classes. To make what they are learning more impactful, school librarian Jennifer Beaver has gotten the eighth graders involved in commemorating the lives of those lost in the Holocaust.

With Jan. 27 being International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Beaver got busy planning some special events this month for the eighth graders. She decided to get the students involved in the Daffodil Project, which is a worldwide project in which groups of people plant daffodil bulbs in remembrance of those who perished during the Holocaust. Over winter break, Beaver met with the Charleston Jewish Federation to receive daffodil bulbs for the eighth graders to plant on school grounds. The students started planting the garden on Jan. 16. The goal is to keep adding to the garden each year.

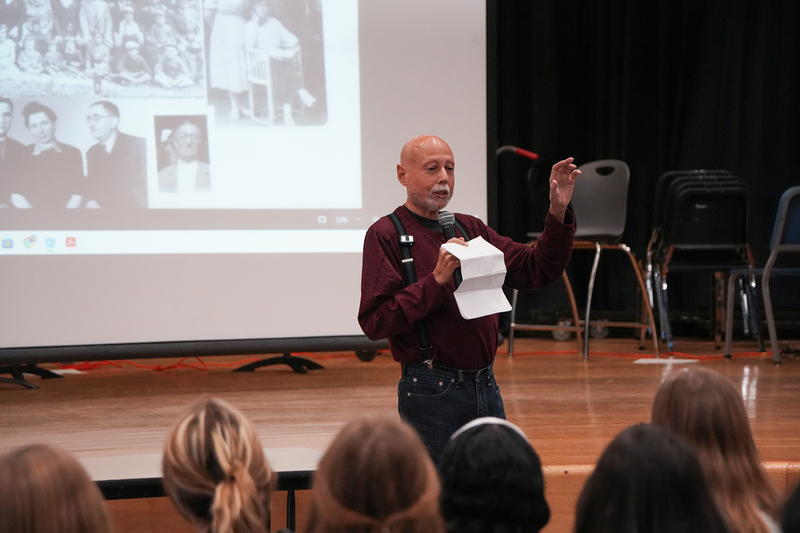

Beavers’s efforts did not stop there; she also got two special guest speakers to visit the school on Jan. 21 to share how the Holocaust affected their families’ lives.

Shirley Mills is the daughter of two Holocaust survivors. Born in a refugee camp in Italy and then raised in Israel, Shirley came to the United States as a young teen. She was a teacher in Cincinnati. Her parents‘ story is one of pain, hope, amazing courage and resilience. In their memory, she shares their story because she feels that: "Humanity has not learned from the past."

Fred Volkman is also a child of two Holocaust survivors whose family members were murdered by the Nazis. His mother escaped a Polish ghetto and then went into hiding with her uncle until the end of World War II. His father briefly worked with the Polish underground, but was captured and placed in various work camps until he was transferred to the Flossenburg concentration camp. Volkman continues their legacy by sharing their story with students and community members and serving on the REMEMBER Program.

Beavers said she believes history can be hard for students to imagine at times, and even harder to understand the depths of such events.

“Locally having people that had firsthand experience with the Holocaust really kind of gave meaning to what they’re studying in English class,” she said.

Beavers added that sometimes empathy is a tough concept to teach, and hopes the speakers’ stories will resonate with the students.

“We definitely want children to see and identify things that are going on in the world and they can be upstanders,” she said. “They can stand up for other people – even friends in class.”

Shirley Mills

Shirley Mills is the daughter of the late Moshe and Rachel Silberstein.

Moshe grew up in the Polish resort town Otwock, where his large, tightknit family owned a bakery. He was married and had a 5-year-old daughter.

In September 1939, the Germans invaded Poland, and in November 1940 closed the Warsaw Ghetto to the outside world. The initial population of the ghetto was 450,000 confined to an area of 760 acres. Escapees were shot on sight. At this point, Moshe was 29 years old, married with a 5-year-old daughter. Moshe would crawl through sewers to get to the other side of the ghetto and would barter whatever he could to get food to feed his family.

Telling the story to the eighth graders, Mills said her father one day returned from the sewers and was met with an eerie silence in the ghetto. He ran up to his apartment building to find doors thrown open, mattresses and clothing tossed everywhere, and his wife and daughter gone – along with his extended family.

Moshe would later tell Shirley: it was the first and only time in his life that he wanted to die, realizing his entire family was taken.

His 19-year-old brother, Meyer, survived by hiding on the roof of the building, and informed Moshe that everyone was taken to the train station. The brothers ran to the station hoping to catch up to their families, but the train had already left. Someone cruelly remarked to the brothers, “You’ll only see your family in the smoke that comes out of chimneys.”

A week later the brothers were put on a train as well, with 80 to 100 people crammed into cattle cars. Mills said Nazis would play a “game” where they would shoot into a cattle car and see what they hit; Meyer was shot in the thigh, and Mills said this injury would cause him to suffer chronic leg pain for the rest of his life.

Upon arriving at Auschwitz, prisoners were sorted into different groups by Josef Mengele, also known as the “Angel of Death” who performed horrific procedures on prisoners during the Holocaust. Moshe noticed that those who were sorted to the left consisted of children, the elderly, disabled people and people of color. Everyone on the right looked like they were fit enough to perform labor.

Moshe pleaded with Meyer to straighten out his wounded leg, worried Mengele would notice and send him to the group on the left. Moshe still assured his brother he would follow him into whichever line he was sent to; miraculously, Meyer was able to straighten out his leg, and the brothers went to join the group of laborers. The other group was sent to the gas chambers for immediate execution.

The laborers had their heads shaved and tattooed; Meyer received a number but Moshe received a KL, which stood for “Konzentration Lager” (“concentration camp”).

Mills told the students that her father and uncle actually were not at Auschwitz very long and ended up being transferred to multiple concentration camps over time – a total of nine, which was unusual, she said. The last camp they wound up in was Mauthausen in Northern Austria. Moshe worked underground on Messerschmitt jets. Laborers would intentionally put in the wrong parts and screws in hopes of sabotaging the jets. Toward the end of the war, Nazis caught Moshe putting in a wrong screw and severely beat him, resulting in the loss of his hearing in his left ear.

After the American army liberated the camp in May 1945, Moshe and Meyer crossed the Alps to a refugee camp in Italy, which is where he met Shirley’s mom, Rachel. They would go on to get married and have Shirley and her younger sister at the refugee camp before relocating to Israel.

“Think about it,” Mills said to the eighth graders. “People who lost everybody had the hope – the faith – to get married again, and bring children into the world.”

Mills’s mom was only 14 when she endured the horrors of the Holocaust, and was so deeply impacted that Shirley did not have a lot of information to share about her mother’s experience.

“We don’t know what happened,” she said. “She would never tell us what happened. My mother suffered from post-traumatic shock syndrome forever.”

However, Mills also mentioned a sweet story of being 9 years old in Israel, when her mother returned home with an older woman. They were both sobbing. Rachel introduced her children to their grandmother; by chance, the two had reunited at a bus stop. It was the first time Rachel had seen her mother since she was 14 years old.

“It was the most incredible day for me,” Mills said. “Miracles like that happened in Israel all the time.”

Mills grew up speaking Yiddish, a cross between Hebrew and German. In Israel, she spoke Hebrew. When she came to America, she learned English. She went on to major in German and French, and learned Spanish when her family moved to Spain. She grew up knowing a total of six languages.

She was still working as a teacher when she began visiting schools to teach students about her parents’ lives and how they were affected by the war.

“They (children) are our ambassadors,” she said. “We need to teach them: kindness and openness is so important. Accept people for what they are, because we’re all the same.”

Fred Volkman

Like Mills, Fred Volkman travels to different groups to share the story of his parents, Mike and Susan.

Volkman said when he was growing up, his parents were pretty tightlipped about their experiences in the war. Volkman did not know the full story of what happened until 20 years ago when he was in his 50s, after his mother passed away and Volkman went to go stay with his father.

While at his dad’s house, Volkman discovered a letter from a cousin in Israel, discussing the Holocaust. Volkman asked Mike why he and Susan never talked to their children about their experiences, and his father replied that Susan did not want to discuss it.

A couple weeks later, Volkman had returned home, and received a letter in the mail from his dad: 25 pages, front and back, detailing what he and Susan endured.

“It was very emotional for me to read it,” Volkman said. “I know a lot about my dad’s story, a little bit about my mom, so I’ll start with my mom.”

Volkman shared with the students a photo of his maternal side of the family, taken in 1935, when his grandparents celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary. There are 26 people in the picture; a young Susan is seated in the grass alongside several other children, and Volkman said his mother is probably around 12 years old in the photo.

“Of those 26 people, only two survived the war – the rest of them were murdered by the Nazis,” he said.

Susan was living in a little village in Poland when the Germans invaded. Susan and her uncle – the other surviving family member from the family photo – were made to live in one of the ghettos. The uncle had some jewelry and money and used it to bribe their way out of the ghetto, resulting in them living out in the wilderness for a few weeks before they were recaptured and sent back to the ghetto.

They bribed their way out again and went to live in the countryside. Volkman said there were gentiles living in the countryside willing to take in escaped Jews and let them hide on their farms – which was a great peril to them as well, because harboring Jews would get them killed. For several years, every few weeks or so, Susan and her uncle went from one place to another to remain undetected.

When word got out that the war was over, the Allies set up displaced persons camps where people could go and get healthcare and recover. Susan and her uncle managed to get to one of those camps.

Unfortunately, that is pretty much all Volkman knows about his mother’s story, other than the rest of her family was sent to Auschwitz and murdered there.

Meanwhile, Mike was part of a middle-class farming family. In1941, the Nazis reached the area of Poland where he lived. Everybody was arrested, and Mike and his brother Larry were separated from the rest of the family, who were sent to concentration camps and subsequently murdered.

Mike and Larry were put into a labor camp, working 12-hour days building roads and given very little food. One day, the Gestapo (or Nazi secret police) grabbed Mike and took him to Nowy Sącz, where they tortured him for three days as they suspected he was helping the partisans or resistance fighters during the war. After not getting anything out of him, they threw him back into the work camp.

In reality, Mike actually was helping the partisans, serving as an informant at night by sneaking past the guards to deliver messages to partisans waiting in the woods.

In 1942, the work camps started closing up. Mike and Larry were relocated to a concentration camp in Mielec, where – like Shirley Mills’s dad – they worked on building Messerschmitt jets.

When Josef Schwammberger took over the camp, the conditions worsened for the prisoners. Schwammberger had some prized race horses that he kept in a barn on the premises. One night, a few prisoners got out, entered the barn and shooed the horses toward the electrified barbed wires surrounding the camp, causing them to break through the fencing and subsequently allowing some prisoners to escape. The Nazis was able to recapture some of them, and then Schwammberger personally shot all of them. When that was all over, Mike and Larry were among the prisoners forced to bury the bodies and then head back to work.

After this event, all the prisoners were tattooed with the letters KL so that if they ever did escape, they would be identifiable.

Years after the war, when Mike was married to Susan and living in Chicago, he was called to testify against Schammberger in Germany. He was nervous to go, but was able to testify from the German consulate in downtown Chicago, and Schwammberger went to jail for the rest of his life and died in 2004.

When the Mielec camp closed, Mike and Larry were transported to another camp called Flossenburg to continue working on roads and machinery. Sadly, three months after arriving at the camp, Larry succumbed to typhus, leaving Mike completely alone.

As the Germans began to realize the war was coming to an end, concentration camps started shutting down and the soldiers attempted to relocate the prisoners. At Flossenburg, Mike was put into another boxcar, with German soldiers manning the cars. Up above, American planes flew over and saw what they thought was Nazis transporting soldiers, not prisoners, and unwittingly began bombing the tracks and shooting at the trains. Many soldiers and prisoners were killed, and the surviving prisoners were sent on a death march.

Faced with the decision to march and die or try and escape, Mike made a run for it in the woods. He was shot twice in the neck and left for dead, miraculously waking up in the care of the Red Cross barracks.

“My dad was a religious person before the war, and this just made him more religious, because he figured it was a miracle that he got saved,” Volkman said.

Eventually Mike found work with the United Nations relief effort. He helped transport supplies to different displaced persons camps, and eventually met Susan at one of them.

Volkman said he started sharing his parents’ story after his father passed away about 10 years ago. His mission is to get students to understand that such atrocities that have occurred in history can happen again.

Despite the devastation his parents endured, Volkman also wants students to learn not to harbor anger, and instead look forward to building a hopeful future.

“My dad went through all sorts of horrible things and yet he was kind,” Volkman said. “Many survivors I have met were kind and started new lives…You can’t forget about it, but you can move on and look toward of the future and be kind to other people – and be hopeful.”